How To Select a Custom Shirt Fabric - Your Comprehensive Guide

Caveat EmptorShirtings, A Primer: Fabrics for Shirts and Blouses

|

||

|

Shirtings, to set the definitions correctly at the outset, are the fabrics from which shirts, blouses, and pajamas are made. Shirtings are not shirts. |

||

|

Disclaimer: I am a shirtmaker and tailor, not a textile engineer. This article is written from my 45+ years of experience creating fine clothing and is as accurate as research, practical experience, rumor, innuendo, bravado, and arguing with vendors can make it. |

||

|

Questions constantly arise involving the differences amongst broadcloths, poplins, oxfords, twills, basket weaves, voiles, gabardines, dobbies, jacquards, and other lesser-known types of shirtings. Here I shall explain what each type is, the differences between it and other types, and in some cases the advantages or disadvantages of each type. You cannot understand fabric types and quality without a basic knowledge of the manner in which cloth is woven: Fabric is made of yarns which run in two directions. In the length, the yarns are known as the warp. The warp is made by winding up thousands of yarns on a large metal roll called a warp beam. These yarns are then threaded into the loom. The other yarns run across the fabric and are known as the weft. These yarns are actually (usually) one long yarn on a cone which is fed in sideways through the warp yarns. This photo shows the basics: |

I know, I know. The photos are very old. But ... they're not quite as old as I ... so live with it! I know, I know. The photos are very old. But ... they're not quite as old as I ... so live with it!

|

|

|

Back in the old days weaving was a much more mechanical process than it is today. The shuttle of old was a wooden device which had points on both ends and a spool of yarn in the middle. It literally flew back and forth across the loom going in-between the warp yarns. The faster it traveled, the greater the strain on the yarn coming off the spool. If it ran too fast, or came to a weak spot in the yarn, the yarn would break. The loom would have to be stopped, the broken end tied (by hand) back to the yarn it broke from, and the loom restarted. Practical experience netted the realization that about the smallest yarns which could withstand this process were the 120's ... and then only if the loom was run quite slowly.

|

||

|

||

|

Before discussing the specific types of cloth, there are three factors which influence all of the types. These factors are: |

||

|

||

|

PLY This is known as Two-Ply Yarn. The twisted Two-Ply yarn resists the normal tendency of yarn to 'pill'. Therefore, fabrics woven of this Two-Ply yarn will have a much greater durability and longevity than fabrics woven of "Singles", or yarns which have not been plied. Where the unscrupulous prey on the unsuspecting is by using a Two-Ply yarn in one direction of the cloth and a Single Yarn in the other direction and calling it "Two-Ply". True high quality cloth uses Two-Ply yarns in both the Warp and Weft directions and is known as 2x2. And to further enhance/complicate the matter, Switzerland's Alumo released the first 3x3 shirting, Salvatore Triplo, in 2008. |

||

|

COUNT OF THE CLOTH Confusion often (purposefully!) reigns between the "Thread Count" and the "Yarn Number". The improperly named "Thread Count", which is correctly termed "Yarn Count", consists of the number of yarns-per-inch in the Warp and the number of yarns-per-inch in the Weft. This determines whether the cloth is loosely or tightly woven. For example, common high-quality broadcloths have a Count of 144 x 76, or 144 Warp (lengthwise) Yarns per inch and 76 Weft (crosswise) Yarns per inch. Logically - assuming the yarn size remains the same - the fewer the yarns-per-inch, the more space there will be between the yarns and the sheerer the resulting cloth. |

||

|

YARN NUMBER This is the number most commonly bandied about ... and usually confused with Thread Count. For cottons, using the most commonly accepted numbering system, yarn numbers run from 24's (thickest and coarsest) to 300's (thinnest and finest). Here, as a difficult to view comparison, is a 100's right next to a 200's. If you look carefully, you can see the thickness of the red plaid 100's yarns on the left is almost double that of the wine striped 200's on the right. The thinner yarns can be spun only from the thinnest, smoothest, longest cotton fibers, known in the trade as E.L.S. or Extra Long Staple. It is the rarest and most expensive cotton grown in the world, comprising in total well under 1% of all the cotton produced. Naturally, the thinner the yarn the softer and more supple the resulting cloth. |

|

|

|

One final note about yarn number. During the past few years, a great amount of "high number" Chinese cotton has flooded the "high-end" market. Although ostensibly 200's, this cotton is of much lower quality than the Egyptian. Much of it is being woven in China and Turkey. The better Italian and Swiss mills still use the Egyptian. As an indicator, in 2008 raw Chinese 200s cotton cost about $1.60/pound while the Egyptian varieties were in the $4.50/pound range. A word to the wise: Inquire about the country in which the fabric was woven. You want to hear "Swiss" or "Italian". That will offer a good indicator of quality. Want the best indicator? Ask the name of the weaver. You want to hear Alumo (#1), Albini (#2), and, following in no particular order, Carlo Riva, Bonfanti, Grandi & Rubinelli, and Testa. Having the extreme luxury of choice at this point in my career, I use mainly Alumo with a bit of Albini.

|

||

|

BROADCLOTH or POPLIN (or Popline fr.) |

||

|

Ha! Thought you were finally going to find out the difference, eh? Well, you're

|

This diagram illustrates the Broadcloth/Poplin construction. |

|

|

To the right is an actual broadcloth example. You can easily see the simple over-under-over repetition. To answer a recent question, MESH is usually made using the same plain weave construction as a broadcloth although I have seen some in a basketweave. The main differences are that the yarns are usually much thicker and are spaced much farther apart. Have a fabric question you'd like to see answered here? Just ask! |

|

|

|

PINPOINT, OXFORD, & BASKET WEAVE |

||

|

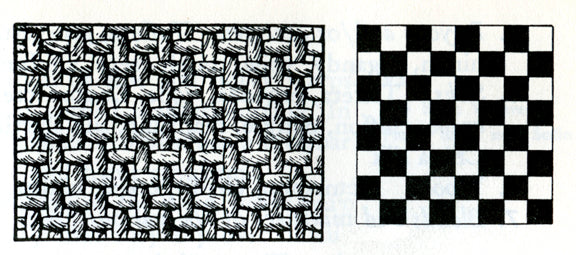

Pinpoint is a very simple type of Oxford - of which there are dozens - almost a broadcloth in nature. The only usual difference between broadcloth and pinpoint, which is woven of broadcloth type yarns, is that the weft thread passes over two closely-spaced warp yarns before passing under two and then repeating. Oxford, named for Oxford University by the Scottish mill which first wove it, is a basket weave. These range from simple, plain Oxfords, usually woven - except in the case of white - from two different colored yarns to the most intricate weaving imaginable. In most instances, the second color of yarn is white. Basket weaves are simple weaves. What differentiates them from the plain weave is that each warp and/or weft yarn passes over and under multiple yarns. These multiples generally range from two to four and can create quite an exciting array of fabrics. To the right is shown the basic weaving patterns for 2x1 and 2x2 Basket Weaves. Do not confuse these denominations with ply - they signify how many yarns are being passed over and under. |

|

|

| On the right is the weaving diagram; the left an illustration of the yarns. The upper diagrams illustrate the 2x1 construction where one weft (crosswise) yarn passes over and under two warp (lengthwise) yarns; alternating which two to pass over or under in each succeeding row. The lower diagram shows the 2x2 construction where two weft (crosswise) yarns pass over and under two warp (lengthwise) yarns; again alternating which two to pass over or under in each succeeding row. | ||

|

Here are three illustrations in actual cloth of Oxford & Basket Weave constructions: |

A 2x2 (ply) 140's Thomas Mason Royal Oxford which is a very fancy construction, indescribable in lay terms but consisting of four yarns in each direction. Some pass over two yarns, others over four. |

|

|

Suffice it to say that there exists a huge array of different Oxford constructions, all of which are characterized by the basket weave construction and most of which are made from at least two different colors of yarn. |

A 4x4 weave, 2x2 ply 80's Oltolina Oxford called Duke |

|

|

One overarching characteristic of most of the fancier Oxfords, or basket weaves, is that their irregularity tends to decrease their durability. As will be noted below in the Satin description, the more warp or weft yarns its crosswise partner passes over, the more chance there is that the untethered, "floating" yarn may catch, or snag, on an external sharp protrusion such as a splinter or broken fingernail. |

A white basket weave, so complex it would require a microscope to unravel |

|

|

TWILL: GABARDINE, CAVALRY, & HERRINGBONE |

||

|

Yup. They're all the same. Twill is the weave type; Gabardine, Cavalry, and Herringbone just various manifestations thereof. A Twill is characterized by the weft (crosswise) yarns passing over multiple warp yarns and then under one warp yarn. The succeeding row does the same, but begins one warp yarn later, etc. This creates a pronounced diagonal rib effect as is seen in this weaving diagram: |

|

|

|

Here are a few simple examples of actual twills of an equilateral and regular weave construction. The topmost, shown to the right, is a Hounds tooth patterned twill. |

|

|

|

A so-called Tick weave in a twill construction: |

|

|

|

A very fine 2x2 170's twill cloth from Alumo: |

|

|

|

Finally, a very heavy Cavalry twill: |

|

|

|

In all twills, the diagonal ribs are termed 'wales'.

Two important characteristics of twills are that they are the most durable of cloths and they are the least likely to soil - but the hardest to clean once they do.

Gabardine Twill for shirts is also a regular and equilateral weave characterized by a hard surface finish and usually a high yarn count. A most popular and common twill is the Herringbone, so named for its likeness to the backbone of the fish of the same name. It also utilizes a regular and equilateral twill construction - but the construction reverses direction every certain number of yarns in order that the diagonal ribs change direction by ninety degrees. To the right is the weaving diagram and a magnified example of a herringbone cloth followed by an example of the actual shirting, a 2x2 100s from Thomas Mason (Albini). |

|

|

|

END-ON-END (or fil-a-fil fr.) |

||

|

The variety of available end-on-end cloths is probably immeasurable. In the simplest terms, end-on-end is a plain weave just like a broadcloth. It is characterized by the interspersion of colored yarns with other colored yarns. Right, the most common blue & white broadcloth end-on-end.

|

|

|

|

Though one of the colors is most frequently white, a great diversity of end-on-ends have arisen in recent years. The simplest and most common - the medium blue broadcloth end-on-end often associated with the white collar & cuff style - is constructed from a warp of alternating white and blue yarns and a weft of white yarns. This yields the familiar 'crosshatched' appearance.

What is usually not realized about end-on-ends is that they are not always woven of the standard broadcloth yarns. A few years back, voile end-on-ends were quite popular as well. The red swatch is an example of a voile-end-on-end construction.

|

|

|

|

Though most end-on-ends which don't use white as one of the colors use lighter and darker shades of the same color, for example, sky and royal, I have seen some really strange combinations in recent times - blue & purple with magenta & fuscia, for example - which when finally made up yielded some awesome, unique fabrics.

Another example of a voile, this time in blue, |

|

|

|

Finally, a 200s 2x2 end-on-end, greatly megnified yet with two colors of yarns so fine it is almost impossible to discern the end-on-end construction. |

|

|

|

VOILE ... and its cousin, Zendaline |

||

|

Voile is a most popular Summer-weight fabric among the cognoscenti. As broadcloth, many voiles are plain weaves. The difference in this cloth lies in the manner of spinning the yarn. Voile yarns are spun to an extremely high twist. This high twist causes the yarns to bulk up in a process called creping. It is illustrated to the right with a thick cotton twine. The top shows the twine in its natural, relaxed position, similar to a broadcloth yarn. The bottom demonstrates what happens when the twine is twisted to the point where it doubles over upon itself - exactly like a voile yarn. The fact that the yarns are 'bulked up' permits the use of fewer of them per square inch (a lower yarn count). This corresponding decrease in the quantity of fiber is the property which makes voiles semi-sheer and extremely breathable, for what they have actually become is quite porous. Additionally, this minimal yarn combined with a soft, high twist makes for an extremely soft, supple, and lightweight fabric.

|

|

|

|

To the right is an example of a 2x2 140's 'French Striated' Voile from the looms of Italy's S.I.C.Tessuti. A hybrid of Voile is known as Zendaline. Woven of the high-twist voile yarns in the weft (crosswise), the Zendaline warp is made from Broadcloth yarns. The resulting cloth, for many technical reasons, exhibits the best features of both yarns. Zendaline has an extremely high sheen reminiscent of the finest broadcloths, but retains the soft hand of the Voiles. Among the upper crust of bespoke shirt wearers, Zendaline is one of the 'must haves' in every wardrobe. |

|

|

|

DOBBY & JACQUARD |

||

|

I am treating Dobbies and Jacquards together because they are both methods of achieving the same goal - that of creating a design on cloth without using colors to do so. Their most obvious difference lies in the size of the design they can produce. Dobby looms are capable of producing small, uncomplicated designs whereas Jacquard looms can create the most complex designs of any size desired. |

|

|

|

The Dobby loom, or technique, is a manner of controlling up to 32 different harnesses which permits the degree of variation necessary to produce simple designs. To the right are two examples. The uppermost is a common satin stripe, in this case adorning a blue voile solid.

|

|

|

| The second example is a truly rare piece, a white-on-white woven by David and John Andersen in Scotland during the first half of the 20th Century. It is called 'Clocks'. |  |

|

|

The Jacquard Loom, invented in 1801 by Joseph Marie Jacquard, is a horse of an entirely different color! There are no heddles or harnesses. Instead, there are thousands of fine steel wires suspended from above, the end of each consisting of an eye through which one ... just one ... warp yarn is passed. Then, through the use of an extremely complex series of punch cards, each fine steel wire is individually raised and lowered as the weft thread passes through resulting in even the most complex of repeating designs. On the right is a very complex example in White-on-White: |

|

|

|

Most modern shirtings do not feature designs so complex as to necessitate the use of a Jacquard loom. The small, repeating designs featured in the majority of White-on-Whites, Tone-on-Tones, and simple satin stripes or checks are quite easily accomplished with the 32 harnesses of the Dobby system. Hold on ... we're almost at the end! Just one more type of cloth to go: |

||

|

SATIN

|

||

|

Though a rarity in cotton shirtings, many silk shirts on today's store shelves are of the satin variety. Similarly, satin components are used in the construction of garments such as the tuxedo. Satins are the most delicate and least impervious to snagging of all fabrics. The reason for this is a magnification of the oxford concept of 'floating' the warp or the weft to permit the natural luster of mercerized thread to show. Satin fabrics, as illustrated in the diagram to the right, feature warp or weft yarns floating out above the surface for a distance ranging anywhere from 4 to 16 yarns! As is obvious, the opportunity for snagging one of these floating yarns is enormous ... though in proper circumstance, the use of satin can be quite attractive. |

|

|

|

Though that concludes the description of the common shirting constructions, no such treatise would be complete without a paragraph or two on a couple of the other important factors which influence the quality of fabrics. Someone also told me that it would be a bit disingenuous to write thousands of words about shirtings and show no shirts. |

||

|

A FEW SHIRTS

|

IN CONCLUSION

|

A FEW MORE SHIRTS

|

|

|

THE FINISHING

Although you now know the basics of constructing the cloth, cloth is not ready for the sewing needle until it is "finished". After weaving, fabric then goes through one or all of a variety of 'finishing' processes. These include dyeing, sizing, mercerization, sanforization, and pre-shrinking to name just a few common ones. Each of these processes has a direct effect not only upon the appearance of the cloth, but on its performance characteristics as well. Environmental responsibility has become more and more of an ethos in the arena of fine textile weaving. As of a number of years ago, all of the fabric coming from Alumo, my preferred weavers, conforms to the OkeoTex Standard 100. This means that no environmentally harmful chemicals are used in the finishing processes. You would be interested to note that, previous to this standard, most fabric finishing involved the use of formaldehyde. It is for this reason that many older sewing factories smelled like mortuaries!

Interesting Sidebar - You've probably heard of the 47 common varieties of Scotch whiskey. One of the primary factors in the variety lies in the water used in the fermenting process. Just as with Scotch, water is one of the key components in many of the fabric finishing processes. Not so strangely, many of the fabrics used to be finished in Scotland. Variety in fabric finished was obtained, in part, by the weaver's selection of which of those 47 waters was to be used. Now, thanks to population increases and pollution, that extensive variety of waters is no longer available. Due to this, many of the characteristics of, for example, the "clocks" example above, can no longer be repeated.

LONGEVITY

I have a few yards of some 240s woven for me by Oltolina in the 1990's. In order to do so, the mill said they ran the loom at a rate of 35 meters per day. Even so, there were still some broken weft yarns and the requisite knots therein. And that was the fastest they could be run. Loom speed today is measured in the multiple thousands of yards per loom per day. The better shirtings (Italian, Swiss - best mills) are made on looms running much more slowly. And this is what happens: The faster you run the loom, the greater the inherent tension in the yarns of the resulting fabric. On today's super high-speed looms, microscopic breaks in the yarns are caused. These do not become evident until the tension begins to really relax. This happens when the fabric is wet (in the laundry). As the number of launderings increases, those fabrics begin to degrade rapidly. Fabrics woven on the slower looms - in other words those without the high tension breakage - do not begin to degrade anywhere near as rapidly. Thanks for slogging through.

Copyright © 2003-2021 Alexander S. Kabbaz, All Rights Reserved.

Comments? Questions? The Author will be happy to answer one and all. |

|